5 Ways You Are Messing up in the Gym

by Mark Ginther

1 – Marathon Workouts

Spending hours a day in the gym doing endless sets and reps is at best not necessary and at worst counterproductive. Testosterone levels typically increase during the early stages of a strength-training workout. This increase can be observed within the first 15-30 minutes of the workout peaking and then dropping off significantly after 45-60 minutes. Conversely, the stress hormone cortisol will significantly increase after about 60 minutes, and after 60-75 minutes will become more pronounced. Chronically elevated cortisol levels can result in a breakdown of muscle tissue as well as increased abdominal fat and brain fog.

2 – Redundancy

Doing multiple exercises for a single body part in a single workout is often unnecessary (and can lead to the marathon workouts described above). The goal of training is to stimulate a particular response, not to do every possible chest (men) or glute (women) exercise there is. This is particularly true when the exercises are essentially the same (joint angle, resistance, range of motion, etc.). Training is most effective when it’s aimed at a specific goal: size, strength, injury prevention, etc. The exercises chosen should reflect this goal and for most training goals, one exercise per body part per workout is sufficient.

3 – Making a Maximum Effort Every Workout

This is often typical of teenage boys trying to max out on bench presses or deadlifts every workout. This will typically lead to burnout, overtraining, and possible injury. Even elite powerlifters don’t do this. Westside Barbell advocates doing maximal-effort lifts no more than twice a week (90-100% of current 1-rep max), one day for the upper body and one day for the lower body. Typically, a bench press, deadlift, or squat variation. Using a bench press, for example, one might change the angle (flat, incline, decline), the range of motion (floor press or using blocks), and so on. To avoid stagnation and overtraining, the main exercise is rotated every 1-3 weeks. This ensures constant new stimulus and continued adaptation.

4 – Not Taking Enough Recovery Days

I often see guys in the gym dragging themselves from station to station, massaging their delts between sets, and otherwise looking burnt out. You aren’t getting bigger and stronger in the gym but when you are resting and recovering. To get sufficient rest and recovery between strength-training workouts, it is essential to implement structured rest days into the training schedule. This allows the body adequate time to recover and repair muscle tissue. For most, especially those that are natural, 3-4 training days per week will be enough. In addition to weekly recovery days, it’s also important to take a recovery week off every 1 to 3 months.

5 – Not Changing Things Up Often Enough

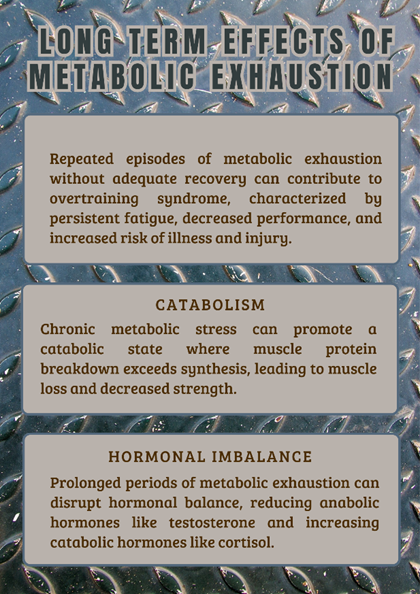

There’s no such thing as a perfect workout program. No single workout can encompass everything one needs to progress and at best will be a compromise. Even the best of programs, because the body will adapt to them, become less and less effective the longer one stays on them. Conversely, the negative effects of a particular workout will accumulate the longer one stays on it, often resulting in metabolic or neural exhaustion, repetitive stress injuries, and so on.

Some will attempt to get around the limitations of a single training protocol by continually adding to their program (without subtracting anything), which will eventually lead to the marathon workouts discussed above. As in example No.3 above (rotating the exercises one uses for a maximum single), the entire workout should be changed every 2-4 weeks (depending on experience and adaptability). These changes shouldn’t be haphazard but within a structured framework; phases, one phase building upon the previous phase. At the beginning of a training cycle, one might start with, for example, an injury prevention phase, followed by a phase for muscular hypertrophy, then maximal strength, and finally explosive power. This concept is the basis for what is known as “periodization of training.”

In Summary:

The errors above can all eventually contribute to burnout, overtraining, and repetitive stress injuries. Finding the optimal amount of training is tricky and is an art as well as a science but if unsure, under-training is preferable to overtraining. Just as the old adage goes, less is often more. Listen to your body and if you aren’t feeling strong and motivated and progress is stagnant, change things up. You’ll feel better and your progress will soar.